Listener Detlef asked if I could give a brief overview of the Byzantine army and describe the changes it went through during the history of the empire. The operative word here is brief but 1.) we’re talking about a millennium and 2.) I’m a former teacher. I’ll try to be concise but you’ve been warned.

Listener Detlef asked if I could give a brief overview of the Byzantine army and describe the changes it went through during the history of the empire. The operative word here is brief but 1.) we’re talking about a millennium and 2.) I’m a former teacher. I’ll try to be concise but you’ve been warned.

Nearly every emperor who reigned longer than a few years made some minor changes to the army and a few- Heraclius, Justinian, Basil II, etc- virtually remade it from the ground up. Usually these significant changes were made in response to some crisis or catastrophe, and they give a nice ‘snapshot’ view of how Rome’s legions became the polyglot mercenaries of Constantinople.

Imperial Rome depended mostly on massive, infantry-heavy legions to do their conquering for them, but by the third century the borders had stopped expanding and the empire shifted to defense in order to keep those pesky barbarian tribes out. It had a hard time doing this because raids came from multiple fronts and the army could only be in one place at a time. Diocletian solved this by reforming the traditional legions into two parts. “Border” units were stationed in forts along the frontier at various choke points to stop or slow down invading forces while more sophisticated, mobile “field” units could be quickly shunted to trouble spots. About a fourth of these field units were cavalry- somewhat of a novelty for the Romans- both heavily armed cataphracts and horse archers for supporting actions. In total, Diocletian’s armies probably numbered about 300,000, spread out along the eastern and northern frontiers.

This basic system remained in place until the fifth century when Justinian reformed the field army. The basic unit was reduced in size to make it more mobile and the army in general began to be much more diverse. In addition to the native troops there were ‘Foederati’- usually barbarian cavalry commanded by a Roman general- and ‘Allies’- groups of Huns or Goths bound by a treaty with the empire to provide service. Unlike the foederati, the allies were commanded by their own officers and fought in their own styles. Justinian also reduced the overall size of the army to cut costs. The total strength of the imperial forces at the end of his reign was probably around 150,000 men despite having more than doubled the empire’s land area.

In the 7th century pressure from the Persians and the Caliphate caused Justinian’s successors- probably Heraclius or his grandson Constans II- to drastically transform the military. The field army was decreased to about 80,000 men (now called tagmata), and instead of border troops in forts, veterans were settled on frontier land. This was called the ‘Theme’ system and it was remarkably successful. The empire no longer had to bear the cost of border troops, but invading armies still had to contend with experienced, battle-hardened soldiers on the frontier.

The Theme system worked so well that the Macedonian emperors were able to go on the offensive and push back the Caliphate. By Basil II’s death in 1025 the field army was probably around 250,000 men, and was far more effective than anything in Western Europe or the Muslim East. Ironically this period also saw the decay of the Themes. Wealthy aristocrats bought up land on the frontiers, and small farmers were increasingly forced out. This process accelerated after Basil’s death and by the 11th century vast estates had replaced soldier communities, completely destroying the Theme system.

The empire filled in the gap by hiring mercenaries- an unhealthy habit that was for the moment backed up by the formidable imperial gold reserves. Meanwhile, civil war and political instability destroyed the Bulgar-Slayer’s magnificent field army, reducing it to a collection of militias, personal entourages, and of course mercenaries. By the time the capable Comneni emperors arrived in the 12th century the army was ruined, and they had to start over. Over several decades they trained a professional, disciplined military roughly 40,000 strong, composed of native troops, levies from the various provinces, and foreign units like the Varangians. It was highly centralized and performed well, but it depended on a competent and strong emperor.

Under the Angeli this type of leadership was conspicuously absent, and the new army was allowed to decay as the treasury was exhausted in lavish spending. When soldiers were needed, mercenaries were brought in or expensive and humiliating truces were purchased. The loss of Asia Minor led to a shortage of men and the Angeli dependence on mercenaries extended to the near suicidal action of disbanding the imperial navy and trusting naval defense to the Italian sea-Republics of Venice and Genoa. The later Angeli desperately gave land grants in return for military service, but abuse of the practice led to feudalization. Provinces started looking to local strongmen for protection and central authority collapsed.

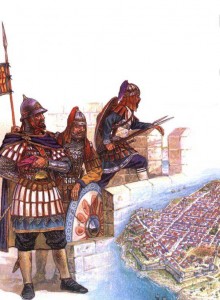

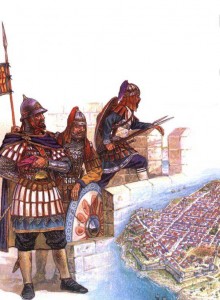

After the 4th Crusade the empire had neither the population to furnish an army nor the money to buy mercenaries, so they relied largely on diplomacy (or a humiliating vassal status) to ward off the coup de grace. When the final end came in 1453, the empire could only muster about 7,000 troops, and a large part of that was the equivalent of Constantinople’s police force. It was a far cry from the 300,000 of a millennium before, but as they so superbly showed, heroism does not depend on numerical strength.

Reader Patricia asks if the Byzantine defeat in 1453 can really be blamed on ‘modern weapons’ since the Byzantines also had access to them. Was it really a matter of simply not having enough money to build them?

Reader Patricia asks if the Byzantine defeat in 1453 can really be blamed on ‘modern weapons’ since the Byzantines also had access to them. Was it really a matter of simply not having enough money to build them?