What was the point of the Byzantine Senate?

It’s the morning after an election and as luck would have it Shane asks a political question- what did the Senate do other than enrich itself and plot?

It’s the morning after an election and as luck would have it Shane asks a political question- what did the Senate do other than enrich itself and plot?

Aristotle first observed that ‘man is a political animal’ and as far as senators go that animal hasn’t changed in more than 2,000 years.

From the beginning Byzantine senators were lured east by the perks- free grain and land at the state’s expense. There were relatively few duties to get in the way of enjoying the good life. While the Roman Empire held on to the conceit that it was a Republic long after any trace of representative government had vanished- as late as the 6th century it was still issuing coins proclaiming the Republic- actual responsibilities were few and far between. There was an obscure clause in one of Justinian’s law codes that said any new law had to be discussed by the Senate, but it was never enforced. Their sole administrative duty was to manage the spending of money on the exhibition of games or public works. This was not a highly lucrative job, so most senators (there were 2,000 of them) used the office for tax reasons- namely to escape the fees levied on others. (the more things change…)

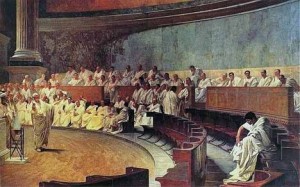

Of course the Senate never quite forgot its august history and there were sporadic attempts to grasp real power. In 532 they participated in the Nika Riots hoping to replace Justinian with one of their own members. (Justinian repaid them by confiscating the Senate House and turning it into a reception hall for the Great Palace.) In 608 they elected Heraclius as Consul, then elevated him to emperor against the usurper Phocas. On his deathbed in 641, Heraclius thanked them by entrusting his young son Heraklonas to their care. The Senate promptly deposed the boy and replaced him with a grandson of Heraclius named Constans II. For the next three years the empire was openly ruled by the Senate- the first time since the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC.

That turned out to be the swan song of senatorial ambition. After Constans came of age their importance quickly declined. The Macedonian emperors stripped them of most of their remaining duties and the Senate was turned into a glorified imperial court. Ordinary criminals were given a jury of 5 senators chosen by lot, while high treason involved the whole body. There was still a whiff of prestige attached to the name, but Alexius Comnenus did away with that by allowing anyone to purchase senatorial rank directly from the emperor.

Their last known act was to elect a man named Nicholaus Kanabus as emperor in opposition to the pathetic Isaac II during the fourth Crusade. Nicholaus- a gentle man- immediately fled to the Hagia Sophia and refused to come out. But his resistance to the imperial summons failed to save him. Another man seized control of the government, and as a warning to any challengers had Nicholaus dragged out of the church and strangled.

Was free grain really extended to the senatorial class? If so, was this done for the entire history of the Byzantine empire?

Not only did the senators get free grain but so did every citizen of Constantinople. Each person was entitled to a certain amount of bread which could be redeemed at the local bakery. This was a huge cost for the state and depended on the grain fields of Sicily and North Africa. When those fell in the late seventh century the free ride was over.

[…] Kanabus as emperor during the 4th Crusade. Their power had been declining for centuries (as detailed here) and their titles were empty, but there were Senators defending Constantinople’s walls on the […]

I remember reading somewhere that Heraclius ended the free-bread hand-outs during the Byzantino-Persian wars of the early 7th century – if this is true, at what point was the policy re-instituted and then abolished?

Also, I know Sir Steven Runciman is not the best source on these matters, but in his book on the fall of Constantinople he describes the Senate has having a role in persuading policy under the Basileus John VIII. Runciman of course does not cite this, which is why I am wondering if he completely fabricated it? (It is on pg. 44, second paragraph.)

Any help would be much appreciated.

I also wanted to ask whether the Trebizond emperors had established a rival Senate to that of Constantinople as Quintus Sertorius had done during the republican era?