View through the bricked-up entrance to the Mausoleum of Alexius Comnenus

Joanna asks which sites in modern Istanbul are a ‘must see’ for Byzantine enthusiasts. For those interested I’ve made a google map (here) of many of the sites- including those outside of Constantinople.

My quick answer is divided into two parts- the “major” ones (if you only have a day) and the “deep cuts” if you have a bit more time.

Let’s get the obvious ones out of the way first. Any such list has to start with the Hagia Sophia (small entrance fee). It is the triumphant masterpiece of the Byzantine world, the place where you can most vividly peel back the centuries to see Byzantium at the height of its magnificence. Walk in through the imperial door- underneath the mosaic of Leo VI- and take as much time as you need to drink it all in. If you can see only one thing in Istanbul this is it.

The Theodosian Land Walls (free): there is a restored section where you can get a sense of what it was like in its prime and if you’re daring there are plenty of stretches for you to climb and explore. Two gates in particular should be visited- the Golden Gate (now incorporated into the Yedikule Fortress) and the Gate of St. Romanus (Topkapi or ‘Cannon Gate’). The latter is where the Turks breached the walls and where Emperor Constantine disappeared.

Chora Church (entrance fee): (Kariye Camii) The original structure dates back to the fifth century but it’s worth seeing for the breathtaking 14th century frescoes. A last glimpse of artistic vibrancy in the waning days of the empire.

Column of Constantine (free): (Çemberlitaş) Known as the ‘burnt column’ in Turkish, it was the focal point of Constantinople. Each year on the city’s ‘birthday’ (May 11) the citizens would gather here and sing hymns. It was raised in 330 and at one time had a huge bronze statue of Constantine as Apollo on top. The emperor buried the most holy relics from the Christian and pagan worlds beneath it- and presumably they’re still there.

Milion (free): Located near the Hagia Sophia, the Milion was originally a double triumphal arch built by Constantine the Great, It was considered the origin point of all roads leading to European cities in the empire, and had the distances to the main cities inscribed on its base. Nearby the Milion was the column of Justinian, the base of which was still visible in the 19th century.

Hippodrome (free): The sporting center of the Byzantine world, the Hippodrome was a witness to some of the most seminal moments in the empire’s long history. Here the citizens of Constantinople gathered to overthrow Justinian during the Nika riots, and here 30,000 of them perished when Belisarius was sent against them. Though little remains of the structure today- apart from one retaining wall- the three columns which once decorated the center of the track are still in place. They are the Obelisk of Theodosius- with a splendid marble base, the Obelisk of Constantine VII- actually much older but sheathed in Bronze by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, and the Serpent Column- the oldest object in Constantinople, it was made from the bronze weapons of the defeated Persians who fell at the Battle of Plataea.

Mosaic Museum (entrance fee): The in situ remains of a floor mosaic from the Great Palace. Offers a unique glimpse of the empire around Justinian’s time.

Hagia Irene (inaccessible unless you know someone): The second church commissioned by Justinian, the Hagia Irene has the distinction of being one of the only churches in Constantinople that wasn’t converted to a mosque after the conquest. An earthquake heavily damaged it in the 8th century, and the great iconoclast emperor Constantine V repaired it, replacing its interior decorations with a monumental cross which can still be seen today. Seldom visited due to severe Turkish restrictions, the church remains one of the few examples of original iconoclastic art. There is a small hole in the bottom of the entrance door that allows a glance inside.

Istanbul Archeological Museum (entrance fee): This is well worth a trip inside (a sarcophagus of Alexander the Great and the lions from the Bucoleon Palace among other things), but the gardens outside are also a treasure trove. Most of the sarcophagi of the Patriarchs and Emperors were evicted from the Hagia Sophia and the Church of the Holy Apostles and those that survived ended up here. Look for the porphyry (purple) ones.

Now for the deeper cuts.

The Church of the Pammakaristos (entrance fee): (Fethiye Camii) The haunting church of the Pammakaristos was refurbished in the 13th century in celebration of the retaking of Constantinople from the Crusaders. Commissioned by the emperor Michael VIII, Pammakaristos contains the largest collection of mosaics outside of Chora and the Hagia Sophia. After the fall of the city, the Patriarch moved the seat of the Patriarchate here, but was evicted five years later when the Sultan had the church converted to a mosque. Many of the original decorations were removed or damaged at the time, but enough remains to give a glimpse of the vanished grandeur of the Byzantine world.

The Myrelaion (free): (Bodrum Camii) If you’re a fan of the Macedonian Dynasty be sure to visit Romanus Lecapenus’ “House of Myrrh”. Intended as an imperial mausoleum for the Lecapeni and as the core of a new Great Palace it was largely abandoned when his family fell from power. Nevertheless it inspired a new building style- the Greek cross-in-square style that most Orthodox churches are still built according to.

Aqueduct of Valens (free): This was the original water source of many of the public fountains and baths in the city, transporting water from the Belgrade forest over 120 km away. According to legend it was built from the stones of the walls of a nearby city that had been pulled down as a punishment for revolt. Repeatedly damaged over the centuries by earthquakes, it was repaired by nearly every famous (or infamous) emperor including Justinian, Constantine V, Basil II, and Andronicus the Terrible.

Sea Walls (free): Though large swaths were destroyed by a railroad in the 19th century, the remaining portions have been turned into a pleasant park. If you exit the city near Sts. Sergius and Baccus you can see masonry from Justinian’s Column in a small gate. A little further is the so-called ‘House of Justinian’- a two story facade of the Bucoleon Palace. Next to that are the remains of the city’s pharos– its lighthouse. The vaults beneath it functioned as the main treasury of the emperors. Follow the walls long enough and you will come the the burial church of Alexius Comnenus (see picture at top of post) built right into the walls. No sarcophagus has ever been found- perhaps he is still there in some hidden vault.

St. Polyeuktos (free): Though now only a rather ill-maintained sprawl of ruins near a highway, St. Polyeuktos was once the largest- and most lavishly decorated- church in Constantinople. Surpassed only by the Hagia Sophia, it was modeled on Solomon’s temple, and filled with inscriptions glorifying its patron’s impressive dynastic credentials. Since she happened to be a private citizen this was seen as a direct insult to the rather low-born Justinian, and may have encouraged the emperor to build his own church on such a massive scale. Upon entering the Hagia Sophia for the first time, Justinian is said to have exclaimed “Solomon, I have surpassed you”- perhaps a veiled reference to his rivalry with St. Polyeuktos. Unfortunately the sumptuous church fell into disrepair and during the Fourth Crusade much of its decoration was plundered. Some columns ended up as far away as Spain and Vienna, but undoubtedly the most famous sculptures taken from St. Polyeuktos are the four porphyry statues of the tetrarchs now included in the masonry of St. Marks in Venice.

Monastery of the Pantocrator (small fee to gatekeeper): This monumental building- the largest built after the age of Justinian- is actually three churches combined into one. The original building was constructed by the emperor John Comnenus in the 12th century and adorned by the ‘stone of unction’- the slab of marble that the crucified Christ had been anointed on before burial. When his wife died, the emperor built an identical church nearby, then added a chapel to connect them. A library and a hospital were attached to the foundation, and it became the mortuary chapel of the Comneni dynasty. After the fourth Crusade it was used as a palace by the last Latin Emperor Baldwin II. Partly ruined today, it can be entered with a small tip to the doorkeeper who usually hovers nearby. This is one of the overlooked masterpieces of the Byzantine world. On the walls are traces of the original decoration- which must have been truly splendid- and on the floor is the marble tombstone of emperor John II Comnenus.

St. John of Stoudios (usually inaccessible): The Studium was the most important monastery of Constantinople, and could claim no less than three emperors among its ranks. Although the monastery has been abandoned for more than half a millennium, several hymns composed there are still in use today in the Orthodox church, and its monastic rule is still used by the monks of Mt. Athos in Greece.

Blachernae Palace (free): Like the older Great Palace, Blachernae was a complex of buildings. Originally the site of a holy spring- and several churches built by Justinian- the last imperial dynasty chose it as the site for their official residence after the fourth Crusade. Unfortunately most of the buildings didn’t survive the fall of the city, but there are still the remains of some dungeons and a few subterranean vaults to be seen. Don’t miss the nearby Palace of the Porphyrogenitus– the finest surviving example of secular Byzantine architecture. Part of the grounds are now used to park tour buses, but the building still boasts fine marble decorations, and a faint wisp of grandeur.

There are many, many more Byzantine things to see- and the only fee most require is a spirit of adventure. But this post is long enough and has been said elsewhere, the joy of Byzantium is in the discovery.

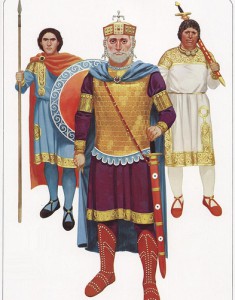

The backbone of the Byzantine army when it dominated the Mediterranean was the feared cataphract. But what exactly- as Joseph asks- was a cataphract? The short answer is the Byzantine version of the knight on horseback. The Roman term was clibanarii which somewhat hilariously translates as ‘furnace’- probably an apt description of what it felt like to wear the armor on a sunny day.

The backbone of the Byzantine army when it dominated the Mediterranean was the feared cataphract. But what exactly- as Joseph asks- was a cataphract? The short answer is the Byzantine version of the knight on horseback. The Roman term was clibanarii which somewhat hilariously translates as ‘furnace’- probably an apt description of what it felt like to wear the armor on a sunny day.