Reader Karen asked why the emperors seemed so fond of mutilation. Believe it or not this was actually seen as a more humane practice of dealing with potential usurpers than the standard treatment of execution. By longstanding tradition only someone of unblemished physical appearance was fit to rule, so a little mutilation (usually blinding, cutting off the nose or splitting the tongue) was an easy way to remove a threat without killing anyone. This held true till the reign of the monstrous Justinian II who was deposed in 695 and sent into exile without his nose. The resourceful man had a gold replacement made and managed to storm Constantinople, taking terrible vengeance on the usurpers. He was given the nickname “Rinotmetos” (the Slit-nosed) and since mutilation obviously hadn’t kept him from the throne, it thankfully fell out of favor. The practice wasn’t completely abandoned, however. Deposed rulers were still occasionally blinded and some emperors- Basil the Bulgar-Slayer comes to mind- mutilated on a mass scale as a way of intimidating their enemies.

Listener John asked why Urban II didn’t lead the Crusade since he seemed to be using it to increase Papal prestige. There were many reasons for his non-participation. He could have used the valid excuse of too many other responsibilities- every crowned head of Europe begged off involvement with this one- but a far better justification was safety. The Crusading army was going to have to walk on foot from Western Europe to Jerusalem, fighting hostile forces nearly every step of the way. The probability of success was remote, the possibility of death or capture was nearly certain, and the thought of the Vicar of Christ as a prisoner of Islam was horrendous. Had the Pope been captured and then forcibly converted the symbolic damage would have been immense.

Listener John asked why Urban II didn’t lead the Crusade since he seemed to be using it to increase Papal prestige. There were many reasons for his non-participation. He could have used the valid excuse of too many other responsibilities- every crowned head of Europe begged off involvement with this one- but a far better justification was safety. The Crusading army was going to have to walk on foot from Western Europe to Jerusalem, fighting hostile forces nearly every step of the way. The probability of success was remote, the possibility of death or capture was nearly certain, and the thought of the Vicar of Christ as a prisoner of Islam was horrendous. Had the Pope been captured and then forcibly converted the symbolic damage would have been immense.

This isn’t to say, however, that it wasn’t contemplated. The idea of a Crusade had first occurred to Pope Urban’s predecessor Gregory VII. His original plan was to lead it in person and leave the German Emperor Henry IV home to take care of the Church. The irony of course is that the investiture controversy almost immediately erupted: the emperor called the Pope a few choice names, the Pope excommunicated (and deposed) the emperor and it was war from then on.

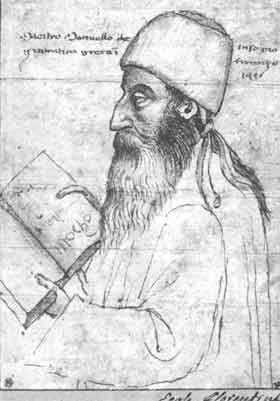

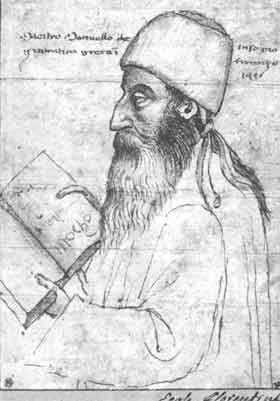

Chrysoloras

Listener Gerardo asked if the Renaissance can really be attributed to Byzantium’s influence. I think it’s going too far to say that Byzantine émigrés caused the Renaissance, but they certainly shaped it. Western Europe was rediscovering its classical past and was fascinated especially by ancient Greece when Byzantine figures like Pletho, Chrysoloras and Cydones arrived. They acted as a catalyst to a movement already underway, tutoring some of the earliest figures of the Renaissance. The study of Greek- which had died out in medieval Europe- was re-introduced and the West was re-acquainted with the giants of Greek learning. The Renaissance would undoubtedly have occurred without these direct Byzantine influences, but it would have been much poorer for the absence.

Listener Allison asked which emperor had the distinction of being the last Roman sovereign to set foot in the ancient capital city. It was the uninspiring John VIII who visited in 1423 to beg for help against the Ottoman Turks. His stay in the Eternal City was quite a contrast from the previous imperial visit. That had been in 663 when the emperor Constans II had visited for 12 days. Despite a stay of less than two weeks, Constans managed to annoy the entire population by stripping everything of value (including the bronze from the roof of the Pantheon) to fund his war against the Arabs. Rumor had it that his tax collectors were so severe that husbands were sold into slavery and wives were forced into prostitution to meet the sums demanded. Fortunately for John VIII, seven centuries tend to dim those kind of memories. He was given a warm welcome and Renaissance artists, taken by his exotic dress left several realistic portraits. Thanks to that Roman trip, he remains the one Byzantine emperor to be realistically painted- a notoriety he certainly didn’t deserve!

Listener Allison asked which emperor had the distinction of being the last Roman sovereign to set foot in the ancient capital city. It was the uninspiring John VIII who visited in 1423 to beg for help against the Ottoman Turks. His stay in the Eternal City was quite a contrast from the previous imperial visit. That had been in 663 when the emperor Constans II had visited for 12 days. Despite a stay of less than two weeks, Constans managed to annoy the entire population by stripping everything of value (including the bronze from the roof of the Pantheon) to fund his war against the Arabs. Rumor had it that his tax collectors were so severe that husbands were sold into slavery and wives were forced into prostitution to meet the sums demanded. Fortunately for John VIII, seven centuries tend to dim those kind of memories. He was given a warm welcome and Renaissance artists, taken by his exotic dress left several realistic portraits. Thanks to that Roman trip, he remains the one Byzantine emperor to be realistically painted- a notoriety he certainly didn’t deserve!

Listener John asked when exactly the office of the Consul died out. The Consulship was the highest office in Republican Rome, dating back to the hazy days in the sixth century BC when the last Etruscan King was expelled from the city. The two elected Consuls held most of the powers of a king, and dates were calculated from the start of their terms. With the rise of the empire, however, it became a largely symbolic office, and was mostly awarded by emperors to themselves. Its prestige was further diminished when later rulers started conferring it on imperial children (Caligula didn’t help matters when he announced that he was nominating his horse) and by the time of Justinian in the sixth century it was allowed to lapse from its yearly appointment. The last politician to hold it was a man with the impressive name of Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius in 541 (that’s a picture of him at the top). He had the misfortune to be in Rome when Totilla and the Goths stormed it, and was forced to flee with his Consular robe into obscurity. That wasn’t quite the end of the office, however. It continued to exist as part of the coronation ceremony for another century. The last recorded emperor to receive the dignity was Justinian II who combined the Consulate with the office of Emperor. From then on the title seems to have been forgotten until the tenth century when the emperor Leo the Wise officially abolished it.

Listener John asked when exactly the office of the Consul died out. The Consulship was the highest office in Republican Rome, dating back to the hazy days in the sixth century BC when the last Etruscan King was expelled from the city. The two elected Consuls held most of the powers of a king, and dates were calculated from the start of their terms. With the rise of the empire, however, it became a largely symbolic office, and was mostly awarded by emperors to themselves. Its prestige was further diminished when later rulers started conferring it on imperial children (Caligula didn’t help matters when he announced that he was nominating his horse) and by the time of Justinian in the sixth century it was allowed to lapse from its yearly appointment. The last politician to hold it was a man with the impressive name of Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius in 541 (that’s a picture of him at the top). He had the misfortune to be in Rome when Totilla and the Goths stormed it, and was forced to flee with his Consular robe into obscurity. That wasn’t quite the end of the office, however. It continued to exist as part of the coronation ceremony for another century. The last recorded emperor to receive the dignity was Justinian II who combined the Consulate with the office of Emperor. From then on the title seems to have been forgotten until the tenth century when the emperor Leo the Wise officially abolished it.