James asks (with exquisite timing) if I’m going to write a book about the Normans. Not only is the answer yes, but for the next week (till Thursday the 22 of May) it’s running under a promotional price of $3.99 from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Writing a book is both about telling a story and finding an ‘angle’ – and one of the most interesting things for me was in telling a familiar story (the Byzantine revival under the Comneni Dynasty, the First Crusade, etc) from the Norman perspective. As a fan of Byzantium, characters like Guiscard, Bohemond, and William I were always the bad guys, dangerous thugs that successive emperors had to dance around to avoid being conquered. But the Normans of the south had to do their fair share of dancing too, and for one brief moment they not only mastered it, but outshone Constantinople itself. Palermo during its golden age had a splendor all its own.

Tancred de Hauteville’s claim to fame is his remarkable fecundity. He produced at least twelve sons, three of whom (William Iron-Arm, Robert Guiscard, and Roger the Great Count) would achieve nearly legendary status and go on to found the richest kingdom of the medieval Mediterranean world. But what happened to the other nine?

Tancred de Hauteville’s claim to fame is his remarkable fecundity. He produced at least twelve sons, three of whom (William Iron-Arm, Robert Guiscard, and Roger the Great Count) would achieve nearly legendary status and go on to found the richest kingdom of the medieval Mediterranean world. But what happened to the other nine?

All but three of them eventually made their way to southern Italy. Since Tancred had two wives (Muriella and Fressenda), the family was effectively divided into two generations. Tancred’s first wife (Muriella) gave birth to five sons: Serlo, Geoffrey, William, Drogo, and Humphrey, while his second wife bore the next seven: Robert, Mauger, William (the younger), Aubrey, Humbert, Tancred, and Roger. The oldest boy Serlo (some sources call him the youngest) displayed the family penchant for fighting at an early age. After killing his neighbor over an insult, he was exiled for three years, but by 1041 had rehabilitated his image enough to inherit his father’s entire estate. This meant that the other boys had to seek elsewhere for their fortune, which started the exodus south.

Geoffrey left first with his half-brothers Mauger and William (the only two who seem to have gotten along with the older generation), and was present at the battle of Civitate where the Normans decisively defeated the Pope’s forces. All three of them were rewarded for their part in the struggle. Geoffrey was made Count of Apulia which he held until his death around 1071 (the same year his oldest full brother Robert Guiscard conquered Bari and evicted the Byzantines from Italy). His younger son Ralph crossed over to England with the Conqueror and was present at the Battle of Hastings. He would eventually settle in Wiltshire and found the English branch of the family.

Mauger got the old Byzantine Province of Foggia, but he didn’t enjoy it for long. He died shortly after a campaign against the Byzantines and his property went to the younger William who already ruled the Principality of Salerno. William proved quite successful- and by some accounts survived into the twelfth century- but his most important act was to invite his youngest brother Roger to Italy.

The most prestigious of the boys (after the Iron-Arm, Guiscard, and Great Count) were Drogo and Humphrey who both served as Count of Apulia and Calabria. Drogo inherited the position from William-Iron-Arm, and when he in turn was assassinated, Humphrey took up the mantle, triumphantly leading the Normans in the battle of Civitate. Humphrey did his best to contain the ambitions of his half-brother Guiscard, but when that proved impossible he entrusted his sons to him. In the best Norman tradition Guiscard promptly confiscated the inheritances and left the boys to fend for themselves.

The last two brothers- Aubrey and Tancred- seem to have stayed in Normandy, perhaps inheriting what was left of the family estate. As a fitting endnote, the oldest brother’s son (Serlo) made his fortune helping the youngest brother (his uncle Roger) conquer Sicily. Young Serlo fought notably for at least twelve years before he fell in an ambush. The place where he was killed- a large flat rock carved with a simple cross- was named after him for nearly nine centuries before a construction firm blew it up in the 1960’s.

If the Normans of the 11th century are to be believed, Tancred de Hauteville was a boar-slaying, righteously glorious knight who sired 12 sons and at least two daughters. Most of those children headed south to make their fortunes in Italy, and their story is covered in the Norman Centuries podcast. But what about those who remained in Normandy? Listener Shane asks what we know about the 4 children who stayed behind.

If the Normans of the 11th century are to be believed, Tancred de Hauteville was a boar-slaying, righteously glorious knight who sired 12 sons and at least two daughters. Most of those children headed south to make their fortunes in Italy, and their story is covered in the Norman Centuries podcast. But what about those who remained in Normandy? Listener Shane asks what we know about the 4 children who stayed behind.

Our three main primary sources for all things Hauteville are Geoffrey Malaterra’s The Deeds of Count Roger, William of Apulia’s The Deeds of Robert Guiscard, and Amatus of Montecassino’s History of the Normans. All were composed between 1080 and 1099, and deal mainly with the Normans in Italy, which means that we know next to nothing about those who opted to stay at home. (Despite later attempts to make the patriarch into a figure worthy of his son’s accomplishments, no one in Normandy at the time cared enough about an impoverished knight to record anything about him). The only one who mentions the remaining sons at all is Malaterra, who simply lists the names Aubrey, Hubert, and Tancred jr, and then moves on. Two daughters (Beatrix and Fressenda) are mentioned because of the husbands they married (Fresseda especially played an important part in early Norman politicking). The only exception to this informational blackout, concerns the oldest brother Serlo. Malaterra mentions that he ran afoul of the Duke (Robert the Devil- William the Conqueror’s father) for murdering a man. In exile he occupied himself with the family business of piracy, raiding Normandy repeatedly. After a suitably heroic display of valor against a local French champion (single combat naturally), Serlo wins over Duke Robert, who realizes the error of exiling such a knight. Serlo pledges his loyalty and presumably settles down into a wealthy, well-respected life- the Norman equivalent of happily ever after.

Due to the paucity of source material, there really hasn’t been any historical writing on these sons of Tancred who stayed in Normandy. (For that matter there hasn’t been much about any except Guiscard and Count Roger). But if historical fiction is more to your taste, there is at least one option. The Words of Bernfrieda: A Chronicle of Hauteville by Gabriella Brooke tells the story of a handmaiden of Tancred’s daughter Fressenda and the clash between the brothers Guiscard and Roger. Since women are almost completely ignored in our primary sources, I think it’s fitting that in this case the two most famous siblings are footnotes in their sister’s story.

Jack asks if the Normans of Sicily spoke French or Italian. Roger I and his successors spoke the Norman dialect of French. But though this was the court language it wasn’t adopted by most subjects. (In a similar manner Norman French became the ‘official’ language of England for roughly two centuries, but the wider population retained their Anglo-Saxon) Most of the Norman’s subjects spoke Greek or Arabic, and continued to do so. The greatest linguistic influx was Italian as the Norman kings brought in mainlanders to repopulate land abandoned by the Saracens. Gradually this formed a unique language- Italian with loan words from French, Greek, and to a lesser extent Arabic. This Sicilian dialect still persists, though of course with modern communications and mobility its future is uncertain. Mainland Italian is taught in schools and the younger generation of Sicilians are much more likely to speak it then their regional dialect.

Jack asks if the Normans of Sicily spoke French or Italian. Roger I and his successors spoke the Norman dialect of French. But though this was the court language it wasn’t adopted by most subjects. (In a similar manner Norman French became the ‘official’ language of England for roughly two centuries, but the wider population retained their Anglo-Saxon) Most of the Norman’s subjects spoke Greek or Arabic, and continued to do so. The greatest linguistic influx was Italian as the Norman kings brought in mainlanders to repopulate land abandoned by the Saracens. Gradually this formed a unique language- Italian with loan words from French, Greek, and to a lesser extent Arabic. This Sicilian dialect still persists, though of course with modern communications and mobility its future is uncertain. Mainland Italian is taught in schools and the younger generation of Sicilians are much more likely to speak it then their regional dialect.

Shannon asks when the term Normans was first used. Unfortunately there are no surviving written records of the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, so we don’t conclusively know what their contemporaries called them when they first landed on French soil, but it’s a safe bet that they were always referred to by some variation of ‘Norman’. Rollo and his immediate followers came from Norway, Denmark (and possibly) Sweden- a relatively spread out geographic location- so they collectively called themselves the Northmen. (The term ‘Norman’ comes from a viking word meaning ‘Norseman’ or ‘Men of the north’- so it would also have been a perfectly natural label for the Franks to apply to the incoming raiders from the top of Europe.) The viking word was latinized to ‘Nortmannus’ which in turn became ‘Norman’. We know they adopted this name because (fortunately for us) the Normans loved to hear stories about their earlier heroes, and the subject of the first major Norman writer (Dudo of Saint-Quentin @1020) was his own people. Showing typical creativity he titled his history of the Normans ‘Historia Normanorum’.

Shannon asks when the term Normans was first used. Unfortunately there are no surviving written records of the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, so we don’t conclusively know what their contemporaries called them when they first landed on French soil, but it’s a safe bet that they were always referred to by some variation of ‘Norman’. Rollo and his immediate followers came from Norway, Denmark (and possibly) Sweden- a relatively spread out geographic location- so they collectively called themselves the Northmen. (The term ‘Norman’ comes from a viking word meaning ‘Norseman’ or ‘Men of the north’- so it would also have been a perfectly natural label for the Franks to apply to the incoming raiders from the top of Europe.) The viking word was latinized to ‘Nortmannus’ which in turn became ‘Norman’. We know they adopted this name because (fortunately for us) the Normans loved to hear stories about their earlier heroes, and the subject of the first major Norman writer (Dudo of Saint-Quentin @1020) was his own people. Showing typical creativity he titled his history of the Normans ‘Historia Normanorum’.

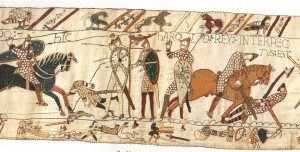

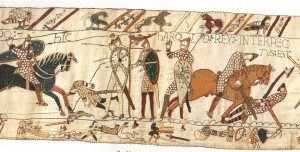

Listener William asks why the Bayeux Tapestry is considered an important or credible source.

There are three main ‘eyewitness’ accounts of the Battle of Hastings- a short poem called Carmen de Hastingae Proelio (made as early as 1067), the Anglo Saxon Chronicle (9 manuscripts of year-by-year events kept at various monasteries across England), and the Bayeux Tapestry. The Tapestry (which isn’t really a tapestry at all), was most likely finished by 1077, and is a goldmine of inadvertent information. Commissioned by William’s half-brother Bishop Odo, it was intended to justify the Norman invasion while casting its two protagonists in a glowing, heroic light. Unfortunately this bias at times compromises the larger credibility of the work. For example, Harold’s coronation is shown being performed by Bishop Stigand, a man whose well-earned reputation for corruption had put a cloud over all of his dealings for years. As an earl, Harold had refused to let Stigand consecrate any of his religious foundations, and it’s unlikely that he would have let the tainted clergyman anywhere near the royal ceremony. His presence in the Tapestry is probably a none-too subtle Norman attempt to further discredit Harold. There are other bias’ in the work as well. Bishop Odo employed English artisans to execute the Tapestry, and there have been several books written about their subversive depictions of the Norman triumph.

But even with these reservations, the Tapestry remains a vital, eyewitness source for contemporary life and warfare in the 11th century. In it we can glimpse the weapons, armor, styles of clothing, and even the pursuits of leisure in the vanished Norman and Anglo-Saxon worlds.

Listener David points out, ‘you called William’s conquest of England the last successful invasion of England by a foreign army. Is that really the case? Didn’t Frenchman Henry Plantagenet invade with local support and force King Stephen to name him as his successor? Didn’t Welsh aristocrat Henry Tudor take the throne as Henry VIII with the help of Lancastrian allies? And wasn’t the “Glorious Revolution” actually a successful Dutch invasion of England? Isn’t it a double standard to categorize any successful invasion that has local support, as a civil war or a revolution instead of an invasion?’

Listener David points out, ‘you called William’s conquest of England the last successful invasion of England by a foreign army. Is that really the case? Didn’t Frenchman Henry Plantagenet invade with local support and force King Stephen to name him as his successor? Didn’t Welsh aristocrat Henry Tudor take the throne as Henry VIII with the help of Lancastrian allies? And wasn’t the “Glorious Revolution” actually a successful Dutch invasion of England? Isn’t it a double standard to categorize any successful invasion that has local support, as a civil war or a revolution instead of an invasion?’

David makes an excellent point here. All of these examples are invasions and can quite rightly be called as such. In each case non-English men seized power in England supplanting the previous dynasty. So calling William the last successful invader is not technically correct. I think there is a valid defense to be made, however, for distinguishing between these examples and what happened at Hastings in 1066. It’s a double standard, but the term ‘invasion’ is usually reserved for a massive social upheaval where an ethnically or culturally different force displaces the native regime. More than just a small change at the top (one related aristocrat for another) it’s a traumatic event that results in widespread effects at all social levels. In that respect, William was the last of a series of invaders: Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and finally Norman. No social upheaval quite so far-reaching has come at the hands of a foreign invader since.

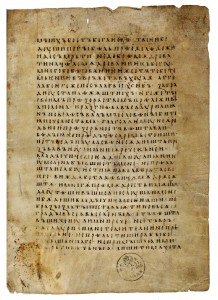

Listener Shane asked if the Normans left behind written works other than histories. The answer is an emphatic yes. They were prolific writers and fortunately we have much of what they produced, especially the Anglo-Norman material. In addition to poems, proverbs, bestiaries, Psalters, commentaries on the Bible, sermons, handbooks, instruction manuals, and hagiographies, we have lyric poetry, satire (mostly poking fun at the clergy or Frenchmen who criticized the English), and Drama like the 12th century mystery “Adam” . Adventure Romances were especially popular (“Ipomedon, Protesilaus, Amadas et Idoine”), but the most famous example of Norman literature is the ‘Song of Roland’- the earliest copy of which is Norman- and which may have been sung by William’s troops at the Battle of Hastings.

Listener Shane asked if the Normans left behind written works other than histories. The answer is an emphatic yes. They were prolific writers and fortunately we have much of what they produced, especially the Anglo-Norman material. In addition to poems, proverbs, bestiaries, Psalters, commentaries on the Bible, sermons, handbooks, instruction manuals, and hagiographies, we have lyric poetry, satire (mostly poking fun at the clergy or Frenchmen who criticized the English), and Drama like the 12th century mystery “Adam” . Adventure Romances were especially popular (“Ipomedon, Protesilaus, Amadas et Idoine”), but the most famous example of Norman literature is the ‘Song of Roland’- the earliest copy of which is Norman- and which may have been sung by William’s troops at the Battle of Hastings.

Listener Shane asked if William the Conqueror and Harald Hardrada had an agreement to attack England jointly. This could after all explain certain curious behaviors by both William and Harald. The Duke delayed his departure to England claiming a lack of favorable winds- was he instead waiting for Hardrada’s attack to draw away King Harold’s forces? Along the same vein, did the Norse invader lower his defenses after Stamford Bridge because he was expecting Harold to be tied up at Hastings? The Normans and Vikings had deep ties and a shared cultural background and it isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that they would act together.

It’s an intriguing idea, but ultimately, I think unlikely. While the close timing of the invasions was certainly mutually beneficial and Hardrada almost certainly knew of William’s plans (he hardly bothered to keep them secret), neither man’s personality was given to sharing. William genuinely believed that he had the best right to the entire kingdom, and while his delay in crossing the Channel proved fortuitous it would be giving him too much credit to say that it was a calculated strategy. Every day that passed with his army still in Normandy cost him in money, food and reputation, and he was as anxious as Harold to resolve the situation as quickly as possible. The more opportunistic Hardrada may indeed have taken advantage of William’s threat, but he was no more likely to share authority than his Norman opponent. He had just finished a fifteen-year war with the legitimate king of Sweden, fought for no other reason than a blatant power grab. This was a man who clearly didn’t tolerate rivals.

If indeed there was an agreement- something like the partition of England that Cnut and Edmund Ironside had concluded a generation earlier- it’s interesting to speculate what would have happened. It would clearly have been a partnership headed for disaster, as neither man would have trusted the other an inch. Only a matter of time and they would be at each other’s throats.

Listener Steve asked “What do you think would have happened had Harold defeated William at Hastings?”

Listener Steve asked “What do you think would have happened had Harold defeated William at Hastings?”

It’s always dangerous to start talking about how history would have been different if a certain key moment had gone differently, but it’s fun to speculate. Harold would undoubtedly have emerged from Hastings with quite a formidable reputation, having held off two full-scale invasions and an earlier series of raids by the Welsh. (King Alfred the Great- the only British sovereign to earn that title- had only managed to keep half his kingdom intact). Normandy, by contrast would have been chaotic- assuming William didn’t survive the battle. It’s amusing to wonder if a strong Harold would have returned the favor and intervened, but the Anglo-Saxons were never as offensively minded as the Normans. It’s also unlikely that they would have invaded either Scotland or Ireland as the Normans did, perhaps at most settling for some sort of ‘over-king’ recognition by the various Scottish clans. That being the case there would be no ‘Act of Union’, no Great Britain and of course no British Empire. England, in fact, would probably have remained part of the northern sphere much like Iceland or Norway. It did have established trading links with the Franks and Low Countries, but both culturally and linguistically it would have been more drawn to the Scandinavian orbit.

Another obvious change would be a linguistic one; the English language as we know it wouldn’t exist (about 60% is Latin or French based) and would be much closer to German . Pre-Conquest England was also generally less efficient and more “democratic” as the King was technically elected by the Witan. William greatly strengthened the monarchy and introduced both feudalism and the distinctive castles that still dot the countryside. Given that the Norman kings were so firmly above the law, democracy may have emerged more quickly under Harold’s descendants- although that’s certainly highly debatable.

Finally, without the Norman Conquest, the English king would not have had a claim to the French throne and would presumably have avoided the hundred year’s war. Without that great unifying struggle the French monarchy would have been weakened and may not have become a centralized state as quickly. While probably not sharing Germany’s fate, France would certainly not have been the power it became by the 17th century.

One could go on and on like this, but the farther we get from the event, the less credible it is. In Harold’s lifetime at least, the people of England would have been much happier if he had triumphed at Hastings.