How did the outnumbered Muslims manage to hold on to Byzantine lands?

Manny asks how the initial Islamic conquerors of the 7th century were able to rule as a numerical minority.

Manny asks how the initial Islamic conquerors of the 7th century were able to rule as a numerical minority.

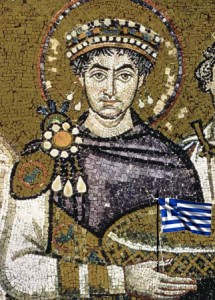

The Byzantine empire in 636- when the first Muslim army arrived- was a remarkably fragile thing. It was militarily exhausted from the bruising war with Persia, and more importantly it had deep internal divisions. Thanks to the interference of Theodora a generation before, the Monophysite heresy had flourished- especially in the provinces of Syria and Egypt which were now filled with religious separatists who viewed the central government of Constantinople as a foreign oppressor. They resented the distant capital for its heavy taxes (trying to recoup the outlays of the previous war) and interfering religious policies. When the Muslims arrived they were seen as preferable for a number of reasons. They were at least fellow Semites, and their religion (initially believed to be a new kind of Christian heresy) was not seen as a threat. Alexandria- one of the 5 great Patriarchates of the Church- voluntarily surrendered, and Jerusalem offered only 3 days of token resistance.

For their part, the Muslims were more than happy to initially rule with a light touch. The subjugated Christians were viewed as a tax base to fund further conquests and there were therefore few pushes for conversion. To most citizens the Islamic victory probably would have changed remarkably little at first. A local Arab governor took the place of the distant emperor but the machinery of government was left in place and literate ‘Greeks’ (the only ones who had the requisite experience) ran the bureaucracy. In some cases the business of administration was carried out in Greek for more than a century after the Arab takeover. The end result for those first centuries was more effective direct rule and lower taxes- and a general unwillingness to return to the empire.

Only after the conquests started to slow did things start to change for the worse for the original Byzantines. Muslim education had caught up to the point where non-Muslims were no longer needed to run the state, and local governments began to focus on conversion. Non-Muslims were second class citizens at best- there were increasingly heavier taxes to pay for the luxury of getting harassed and excluded from many public sector jobs. (A particularly terrible harassment during Ottoman times involved Christian families surrendering one son to be forcibly converted to Islam and enlisted in a special branch of the army) As the burdens got more onerous many took the easy way out and converted. By the time Byzantium recovered in the 10th century and went on the offensive again Islam was too entrenched to expel.