Who were the Varangians?

Listener William asked who the Varangians were and why they figured so prominently in Byzantine military affairs.

Listener William asked who the Varangians were and why they figured so prominently in Byzantine military affairs.

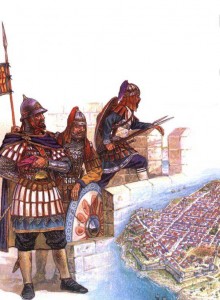

The Varangians were the elite forces of the Byzantine army- much like the Praetorian Guard of ancient Rome or the Ottoman Janissaries. They were originally made up exclusively of Vikings (which the empire had been hiring as mercenaries since the 9th century), but after the Norman Conquest of England a rush of exiled Anglo-Saxons were added to the mix. By the 12th century there were so many English that it was commonly being referred to as the ‘Anglo-Varangian’ Guard. As the empire declined, the Varangians also fell on hard times. By the middle of the 14th century they had largely ceased to function and the last mention of them is in the first decade of the 15th century.

They appeared relatively late in Byzantine history. In 988, the emperor Basil II, facing a serious revolt, asked the Viking prince of Kiev for some help. In exchange for an imperial bride, the prince sent along 6,000 warriors and Basil was so pleased by their effectiveness that he made them his permanent bodyguard. Their oaths were to him personally- a fact that the court was uncomfortably aware of- and they were housed in the Bucoleon Palace where they could keep an eye on things. Basil made sure they were given a generous salary and he called them ‘Varangians’- literally ‘men of the pledge’.

Since they were professional fighters they were the most valuable troops in an army made up mostly of mercenaries or levies. Usually taller and fiercer than their Mediterranean hosts/opponents, they also made good use as propaganda tools to overawe rebellious subjects or frighten opposing armies. In times of peace they could act as a police force in Constantinople or for ceremonial functions. In war they were usually held in reserve until the critical phase of the battle- then sent where the fighting was thickest. Even the Byzantines seem to have been slightly terrified of their berserker rages.

The opportunities for wealth ensured a steady stream of recruits, and few returned home empty-handed. At the death of an emperor they had the curious right to raid the treasury and take away whatever they could carry unassisted. Perhaps because of this they gained a reputation for fierce loyalty to the office- but not necessarily the occupant- of the throne.

At times the temptations of power were too much to resist and they would lord it over the population of Constantinople- usually in the local wine shops. Their drinking bouts were almost as legendary as their fighting skills and a visiting Danish king in the 11th century was embarrassed enough to publicly lecture them about their behavior.

His words do not appear to have had the desired effect. A century later some brave soul referred to the Varangians as the ‘Emperor’s wine-bags’.