What was Byzantine Athens like?

Justin asks how Athens fared during the Byzantine period.

Justin asks how Athens fared during the Byzantine period.

To put it bluntly, Constantinople’s gain was every other prestigious city’s loss. Constantine and his immediate successors looted Athens of much of its impressive works of art, including the famous statue of Athena that graced the Parthenon. This, combined with an exodus of talent (the action was clearly in Constantinople) reduced the city to a shell of itself. The deathblow, however, was Justinian’s closing of the Academy which ended its one remaining attraction as a university town. In 580 invading Slavs burned the lower city and (in a demonstration of how little importance was now attached to the place) it took the empire a decade to rebuild.

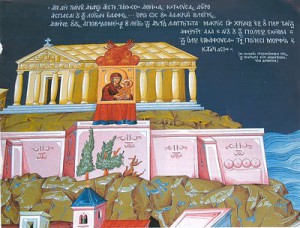

It was probably around this time that the Parthenon was converted into a church. Roman emperors had started making pronouncements in the 4th century to convert all pagan buildings to Christian ones, but these edicts had been largely ignored in the backwater parts of the empire. And Athens was by now a true backwater. Its economy was almost purely agricultural with one or two ‘aristocratic‘ families hanging on, and for the next two centuries it was a sad, little village huddled around the Acropolis. The low point was the early 7th century when Heraclius reorganized the empire along military lines. Needing a capital for the province of Greece (Hellas), he bypassed Athens completely and chose Thebes- a move which would have appalled any ancient Greek who fought at the battle of Plataea.

But the 7th century also saw the city’s fortunes begin to recover. A sign of this was that fact that Heraclius’ grandson Constans II (who knew his Herodotus) spent the winter of 662 there on his way to Sicily. He was on the search for a new capital- the last Roman emperor to seriously consider moving back into the west. (He was attracted by the virtual impregnability of the walled Acropolis) There were also emerging signs of intellectual life. Theodore of Tarsus (who would be Archbishop of Canterbury from 669-690) studied there, and Athens became a haven for monks fleeing Iconoclastic persecution (thanks to the availability of caves in nearby Mt. Penteli). The late 8th and early 9th centuries saw two Athenian women (Irene and Theophano) become empresses- with one (Irene) even ruling as emperor.

By the end of the 9th century the population had expanded enough to make Athens a true city again. The local bishop was promoted to Metropolitan, and the city was finally made the seat of the Theme (province) of Hellas. (You can see a vestige of this period on the Acropolis today- one of the columns of the Parthenon has a carving recording the death of the strategos (governor) Leo in 848) The next three centuries saw a sustained period of growth- the ‘golden age’ of Byzantine Athens. A tzykanion field was installed (an aristocratic game related to polo), and Athenian merchants grew wealthy selling purple dye and soaps. In 1018 Basil the Bulgar-Slayer visited specifically to visit the Parthenon church. His presence (he may have cleared the ruins of the nearby Daphne monastery and begun to build the magnificent dome visible today) kicked off a rash of church building- most of the surviving Byzantine buildings (Church of the Holy Apostles in the Agora, Panaghia Kapnikarea, etc) date from this period.

The new wealth and prestige (and general isolation from the troubles besetting the rest of the empire) led to feelings of independence. They rose against the central government of Michael IV in the 11th century and were brutally suppressed by an imperial army led by the Norse adventurer Harald Hardrada. The city physically recovered quickly (a 12th century Arab traveler reported that it was well populated and surrounded by rich country), but couldn’t escape the wider Byzantine decline. Roger II of Sicily sacked it in 1147, and the new governor sent in 1182 complained that it was filled with ‘uncivilized hordes whose boorish accents took 3 years to learn’. In 1204 came the ultimate humiliation when it was seized by crusaders. For the next 250 years it was ruled successively by the French, Catalans, and Florentines. The Athenians referred to the period of French and Catalan domination as the ‘ultimate slavery’ and things got so bad that Greek had to be reintroduced in 1387. The Byzantines never regained control.

As for the Parthenon, it weathered the ages gracefully. The large statue of Athena was probably removed to Constantinople in the third century where it was set up in one of the public squares. In 360 it was restored by Julian the Apostate in his quest to revive paganism and probably remained a temple for some time after Theodosius’ decree of 379 which made Christianity the sole legal religion of the empire. As a church, the Parthenon attracted both famous pilgrims and the donation of relics. Outside of Constantinople, it probably had the most impressive collection in the empire. (including a painting of Mary done by St. Luke which gave the church its name, and a copy of the gospels written on vellum by St. Helena) The 13th century Italian sightseer Niccolo da Martoni left a breathless description- the magnificent marble carvings, glittering mosaics, massive columns, and the seemingly endless reliquaries. He also repeats a story (smacking of that time honored tradition of local guide yarns) about the doors being made of the wood from the gates of Troy.

Interestingly enough, the Parthenon was a church for longer than it was a pagan temple, since it survived as such until the Turkish occupation of Athens in 1456. As for the famous statue of Athena, that lasted almost as long. It stood in Constantinople for almost a thousand years until 1204. As the crusading army gathered outside the walls a superstitious mob converged on the square where it was kept. Since the statue happened to be facing the West it was blamed for attracting these western barbarians and destroyed.

That of course, was only the beginning of the destruction.

[…] from a mighty capital to a forgotten village. Lars Brownworth provides the reference point – What was Byzantine Athens like? Further reading: What really happens when Greece […]

There is something particularly sad about an ancient and formerly great city in decline. I was in Cairo a few months before the unrest – and I could tell there was a sadness and desperation in the air. That feeling was particularly sad because it was painfulle and obviously juxtaposed to the great achievements of Egypts’ past, ie the Pyramids. I wonder if that same desperation and sadness was felt in the air of Byzantine Athens.

Thank you for answering my question.

Thanks for an interesting response to a great question.